By Miriam L. Zimmerman

This column originally appeared in our July 12, 1995 edition. In remembrance of Eva Kor, who passed away in Poland on July 4th we are posting it now.

Eerily, I recently met what could have been a mirror image of my own family: a doctor, his daughter, the son who followed his father’s footsteps and became a doctor. A beautiful granddaughter. The same German accent of the beloved “Opa.”

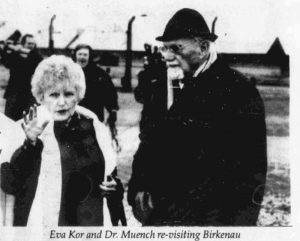

But this family was not Jewish. His name is Hans Muench, and he was a former SS physician who worked at the Auschwitz concentration camp. He was known as “the SS doctor with a conscience.” I met Dr. Muench through Eva Kor, a former Mengele twin and survivor of Auschwitz.

Last fall, Eva had been flown to Germany by television producers and had appeared on talk show with Dr. Muench. They became friends. She asked him to attend with her the 50th anniversary celebration of the liberation of Auschwitz. He agreed.

Eva brought her two adult children, Rina Kor of Ann Arbor, Mich., and Dr. Alex Kor of Evansville, Ind. The Muench entourage included 84-year-old Dr. Hans Muench and his son. Dr. Dirk Muench, a pediatrician who specializes in neonatology. His daughter, Ruli, is my age. She brought her daughter, Iris.

Both Drs. Muench live in Germany. Ruli and Iris live in Canada. We would stay at the Continental Hotel in Krakow, travel to Auschwitz daily for four days on the same private bus, and take our meals together in the hotel dining room.

In addition, Eva assembled a video crew of four from Eastern Illinois University and PBS station WEIU, Channel 51 of Charleston, Ill., to create a documentary film. Eva’s biographer, Mary Wright, and Terre Haute Tribune-Star reporter Tammy Ayre rounded out the media professionals who accompanied us. An Israeli contingent of twins and other survivors were to meet us in Poland.

Last fall when I was arranging with Eva to join this odd assortment of people, a colleague approached me at my new school, the College of Notre Dame in Belmont, Calif. The Rev. Wayne Maro, college chaplain, had been profoundly moved by his visit to the new Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. This experience inspired him to try to join our group.

I called Eva with the request that a colleague who wanted to start a course in Holocaust Studies join us. “By the way, Eva,” I added, “Wayne is a Roman Catholic priest.” There was a pause as she digested this latest piece of information.

“Well,” she considered, “if I can take an SS doctor to Auschwitz, Miriam Zimmerman you can bring a priest.”

In the weeks that preceded our Jan. 23 departure, I became obsessed with preparing for this trip. I finished reading Karen Armstrong’s A History of Cod and began Richard Rubenstein’s After Auschwitz. I spoke with survivors. I even met with my rabbi concerning some doubts about meeting an SS physician at Auschwitz.

How could I so affront the memory of my own physician father, may he rest in peace, by shaking the hands of a doctor who had conducted experiments at Auschwitz? Rabbi Alan Berg, senior rabbi of my synagogue, Peninsula Temple Beth El, advised that I didn’t have to participate. We were walking toward my new office on the lovely forested campus of College of Notre Dame, an oasis of tranquility sandwiched between suburbs of San Francisco and San Jose.

He lent me a small siddur, (prayer book) and suggested that I stop and read from it whenever I felt the need. The siddur was small enough to fit easily into my coat pocket. I felt reassured, armed and anchored by Jewish prayers. I thanked him as I shivered coatless in the light northern California breeze that had brought the temperature down to the mid-sixties, unmindful that soon I would be coping with a wind chill factor that reduced the temperature to 20 degrees below zero.

But our first day at Auschwitz was not representative: temperature was in the 40s, with a pale blue cloudless sky. We started filming at Auschwitz II, also known as Birkenau. Elie Wiesel was standing just outside the infamous red “Gate of Death” through which the cattle cars transported their victims to their final destination.

The camera crew busily captured the images of Eva Kor and Hans Muench describing what had happened, explaining to their adult children what they had experienced. We followed the railroad tracks from the gate to the selection platform. Eva and Dr. Muench measured the length of the selection platform with an enormous Realtor’s tape. It was longer than either of them remembered.

“More families have been torn apart on this piece of real estate than on any other spot in the world,” Eva observed. She wanted its exact dimensions recorded for posterity.

I got caught up in the media frenzy, began snapping as many pictures as I could, feeling that each shot might be my last. I didn’t realize yet how the agenda to make a documentary interfered with my experience of the enormity of the expanse around me.

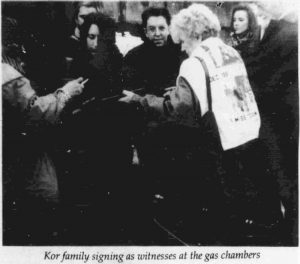

In front of the crematorium II in Birkenau, both Eva and Dr. Muench read and signed prepared statements documenting the atrocities that had occurred there; Eva, from the perspective of a victim; and Dr. Muench, from the perspective of a perpetrator. He documented the gas chambers at Auschwitz, so important in this era of Holocaust deniers.

By this time we had collected considerably more media. At least three different video crews recorded this event. I perched on some rocks, precariously, to obtain a better view.

In her name only, Eva offered amnesty to all Nazi criminals. It was time, she maintained, to allow Nazi war criminals to come forward without fear of reprisal. I spoke with her privately so that I could intimately understand such an about face in her thinking.

“What did you hope to accomplish in declaring amnesty for all Nazi war criminals?” I asked Eva in the comfort of her hotel room on our last night in Krakow. She was tired and ill from the flu that had been recycled throughout the group these last ten days in Poland. But she wanted to talk.

“Dr. Muench and his family… gave me a feeling that we together did something that was very significant. That significance will live on and bear fruit.” By giving amnesty, Eva hoped “that more SS will come forward to testify to their crimes — for the sake of the families that survived and for the sake of history.”

She said there is an important by-product of this process of coming forward to admit their crimes. It will “free them from eternal anger… by saying what they have done, [they will] see it in a different light.”

“Right now they are in denial: ‘I had to do this, I had to do that. It will be helpful to them as well; they don’t have to carry it inside like a secret. Secrets are never healthy.

“I had hoped to spark a debate about what I was doing,” Eva continued passionately. The U.S. press was absent; a big disappointment. Such an important event got left behind.

“If one of us had shot the other [Eva and Dr. Muench], we would have gotten coverage. The press does not want to cover anything positive — but I don’t believe the public wants only violence. I think the public would very much like to see constructive healing ideas. By the press not covering our ceremony, they deny the opportunity for debate.

“A lot of people come up with good ideas; not reported — ideas die. The US national press failed 100 percent.” Eva concluded her indictment of the press with praise for the German media. “At least six German reporters interviewed Dr. Muench and me,” she noted ironically.

The former Mengele twin returned to the theme of forgiveness. “What does not forgiving accomplish?” she asked rhetorically. “Does it make someone feel better? Does it look noble? Does it give answers to what happened? And if all three answers are ‘no,’ why not try something that works better?

“Forgiving — the minute you are able to say I forgive you for what you have done,” it makes you feel you have the spirit to rise above what happened. And that is already a lot better than holding on to the pain.

“At the same time, you are giving the other person the feeling that they don’t have to worry about their crime and they can do something decent in return. I think they — some — will feel obligated, not have to deny or run away from the past.

“We want — deserve — more than these worn out statements: ‘I was just following orders.’ I would like to hear ‘I’m sorry.’

“Instead of hiding behind lies, they can come out straightforward and tell you what happened.

“We know that forgiving makes the forgiven feel better. We are talking about the Jews forgiving the Nazis…

“Does it make the forgiver feel noble? You bet. Try it. You can’t function as well when you are angry. You must release the anger.

“The chances that we will get any answers to what was done to us in the camps if they will testify and go to jail are zero. They won’t testify and commit themselves to life imprisonment. That’s why they lie.

“But if there is no criminality involved with it and it might clear their mind from the burden of the past, we might have some chances of getting answers. Fifty years after Auschwitz, there can be no justice. Justice [for the victims] does not exist. What is the next best thing? Forgiveness and truth.”

Eva Kor held her own press conference, on a much smaller scale than the official one conducted by the Polish government. Both Eva and Hans read their statements. The Israeli camera operator stomped out impatiently.

I spoke with him after the news conference. In response to my asking why had he left, the Israeli cameraman replied loudly, “That SS doctor is a sham. He was there, in Auschwitz. Bullshit he didn’t know what was going on. He’s guilty. They were all guilty.” The anger and hate that radiated from him made me realize for the first time how brave it was that Dr. Muench had come forward to tell history. The Israeli turned on me. “Do you believe him? How can you believe him?” he accused. I wasn’t used to being yelled at in hotel lobbies and backed away.

But the cameraman forced me to re-evaluate how I was perceiving Dr. Muench and his family. I hadn’t wanted to like them, but in the first few days I was struck by their warmth and the authenticity of their interaction. They could have been my family. Indeed, in speech and stature, Dr. Muench brought to mind my own father. The same accent, white hair, and courtliness. At 84, he was the same age my father would have been. I blinked back tears at the comparison. Had I been too uncritical in my acceptance?

I was determined to understand how this SS physician had refused to make selections and gotten away with it. I sat next to him at dinner and asked if I could interview him afterward. It had been a long afternoon in Birkenau, our first day of filming. He must be tired. But he willingly, even eagerly agreed, asking his granddaughter Iris to help translate when his English faltered.

I asked for him to pass me the water decanter. Instead, he took my glass and filled it for me, very gracious, something my father would have done. I recalled the Israeli cameraman’s outburst that all the SS were guilty. I decided not to be taken in by good manners and superficial resemblances to my own father.

Yes, Dr. Muench had volunteered to join the SS. In his statement, he described himself as a “young opportunist,” to further his career. He was 30 years old. He actually was not an Auschwitz physician. Rather, he started out as a house doctor for farmers. Joining the SS was a ticket off the farm.

He happened to meet a university researcher from his school in Dresden, Mr. Strassberger. They worked in bacteriology. That was how he got to Auschwitz, as a bacteriologist. There were epidemics of typhus and dysentery in the camps. The Nazis didn’t care if the prisoners died, but the epidemic had spread to the SS guards and outside the camp. Thus they called in a specialist like Dr. Muench to help contain the epidemics. Dr. Muench worked at the Institute of Hygiene in Berlin, not as an Auschwitz doctor.

“Then how can you say you avoided making selections?” I wanted to know.

He explained mostly in English, that there were so many trains arriving, the Auschwitz physicians could not keep up with the work. By then he had been transferred to another Hygiene Institute just outside of Auschwitz. His superior told him he had to report to Auschwitz because they needed more physicians to make selections.

When he reported to the camp and saw what was involved, he went back to his superior who was also a friend and told him he couldn’t do it. His friend arranged for another physician to replace him. There had been no repercussions, no penalties imposed on him for his refusal.

I asked about the experiments. “It was a formality that patients were killed after the experiments,” Dr. Muench explained. But he was able to save lives by using a method that prolonged the time necessary for the experiments. Some of the victims even survived the war.

Dr. Muench obtained permission from Himmler for the new procedure without explaining to Himmler that in so doing, lives would be saved. Jewish prisoner aides cooperated and understood what he was doing. These aides were often world-renown physicians and scientists. They were the ones who testified on Muench’s behalf after the war.

After the war, Dr. Muench spent 11 months in Krakow prison awaiting trial. He was the only SS physician found innocent of any war crimes in a court of law.

I asked when had he first realized what Auschwitz was like. It was on his second day at the Hygiene Institute near Auschwitz, a kapo had brought the Jewish prisoner medical aides to Muench’s office. Dr. Muench had arisen and walked forward to shake the kapo’s hand when he felt a very sharp slap on his back. The other SS official told him not to touch the kapo, who was, after all, just another prisoner. [A Kapo was a Nazi concentration camp prisoner who was given privileges in return for supervising prisoner work gangs: often a common criminal and frequently brutal to fellow inmates.]

Wasn’t he afraid he would get into trouble by helping prisoners? It was a crime punishable by death. He answered that the SS system at Auschwitz was so corrupt, that after a very short while he realized he could get others into trouble by what he knew. Each SS officer profited illegally from the labors of prisoners under his protection. For example, one SS had carpenters working for him, another had tailors. Even Dr. Muench got in on the action. He had made schnapps from fermented jams and jellies. But what others did was much worse.

It was late, but I couldn’t resist asking about Josef Mengele. Was it true that Mengele was alive in 1982? Yes, Dr. Muench was emphatic on this point. Mengele was alive in 1982. But what about the body discovered in 1985 in Sao Paulo, Brazil? That was Mengele, Dr. Muench confirmed.

But that body had been buried in 1979. If Mengele had been alive in 1982, then the Brazilian cadaver could not have been Mengele. Iris stood up to leave; she was very protective of her grandfather. The interview was over.

I related this information to Eva. She already knew that Muench believed strongly that Mengele was still alive in 1982. Eva shrugged; she was no longer interested in keeping the Mengele issue alive. She had met someone in Germany last November, a friend of the Mengele family, who had seen a recent picture of Josef in women’s clothing. The great Nazi SS doctor “dressed like that to go out in public.” Eva’s amnesty even extended to her nemesis, Dr. Josef Mengele.

On our last day in Birkenau, I jogged the length of the selection platform from the Gate of Death to the crematoria. During those 25 minutes I felt most in touch with my beloved father, of blessed memory, who had encouraged me at middle life to take up jogging. Together, we ran in two San Francisco Bay to Breakers races. This jog is for you, Dad.

I thought of the families Muench and my own Loewenstein clan. How alike, how dissimilar we were; our connection to the medical profession. At the end of his life, my father, a graduate of the University of Berlin Medical School, had made speeches to medical groups about Nazi medicine and the debasement of his profession in the Third Reich. I have inherited all of his speeches, his sources.

At one point, I asked Dr. Muench how many physicians had joined the SS.

Muench hesitated, then answered, “Not many.”

Had I trapped Dr. Muench in a falsehood or should he not be expected to know that physicians had joined the SS in far higher proportions than any other professional group?

Was Dr. Muench, indeed, innocent of any medical crimes? Or was he a sham as described by the Israeli cameraman? My father would have had the tools to judge Dr. Muench. They would speak in German, compare their medical practices.

The conflict raged in my mind as I made the return jog down the length of the selection platform in Birkenau. From a distance, I could see the families of Eva Kor and Hans Muench; they looked like any other families on a Sunday outing.

I tried to make my mind as neutral as possible, like a Zen master. The rhythm of my jogging helped. Dr. Hans Muench was the only SS physician on record who refused to make selections and the only SS physician among about 40 brought to trial in Krakow found innocent of war crimes. Seven of them were jailed and the rest hanged. The resistant part of me acquiesced, and what began as a vague feeling of trust metamorphosed into a recognizable conviction. I believe you, Hans.

Dr. Zimmerman is professor emerita at Notre Dame de Namur University (NDNU) in Belmont, Calif., where she continues to teach the Holocaust course. She can be reached at mzimmerman@ndnu.edu. This column by her originally appeared in our July 12, 1995 edition. You can view it on page 14 (NAT 8) of the following link: https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=JPOST19950712-01.1.14&srpos=13&e=——-en-20-JPOST-1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22