By Tracie Freudenthal-Mrakich

Stolpersteine

On March 21, 2019, my sister Linda and I boarded a flight to Frankfurt, Germany. Packed in my suitcase were three tins, each containing a dozen hamantashen baked by my friend, Beth Valinetz-Grimm. Beth sells thousands of hamantashen every year to benefit the JCC Early Childhood Education program. I also carried a small photo album in my backpack containing a selection of photos of our father’s life in Germany and his family and professional life in Indiana.

After the long flight, we were able to check into our room at 7:30 a.m., local time. Instead of powering through the day on little sleep, we opted for a two hour nap, showered and explored Frankfurt. That evening, we met J Clair for dinner. She had transferred from the NYC Deutsche Bank offices to Frankfurt almost a year ago and is enjoying her new life in Frankfurt, traveling the globe for both work and pleasure and learning to speak German. J Clair treated us to a delicious, traditional German dinner. I also tried Apfelwein, a German hard cider that is popular in Frankfurt.

The following morning, we traveled by train to Mannheim, Germany, about 40 minutes south. Our purpose was to attend the Stolperstein placement/dedication in front of the apartment building where our father, aunt and grandparents lived for many years before immigrating to the United States in late 1938.The Stolperstein (translation – Stumbling Stone) is a 3.9” x 3.9” square concrete cube bearing a brass plate inscribed with “Here lived…” followed by the names, birth year and year and place of death of deported Jews and other groups persecuted by the Nazis.

The Stolperstein project also includes individuals or families like ours who were fortunate enough to leave Germany and other countries that were under Nazi control. “Year fled” replaces the year of death, and the country that allowed them entrance is noted. To date, there are more than 70,000 stones throughout Germany and other European cities that have been placed by artist Gunter Demnig. Four stones would be dedicated on March 26th at Richard Wagner Strasse 8, Mannheim, Germany, for our grandparents, Benno and Kate Freudenthaler, our aunt, Suse (Susan) Freudenthaler, and our father, Kurt Freudenthaler. Our family name was shortened to “Freudenthal” when they were processed at Ellis Island. The stone dedication was the excuse that I did not know I was looking for to visit Mannheim.

What we know…

Picnic in Germany with Kurt’s mother Kate, sister Suse, Kurt (standing) and a friend.

We know very little of our father’s life in Germany. He was 16 when he and his family fled shortly after Kristallnacht. They sailed on the Noordam from Rotterdam on Christmas Eve 1938, arriving at Ellis Island on Jan. 1, 1939. From New York, they made their way to Richmond, Ind., where an aunt who had sponsored the family lived. Like so many German-Jewish immigrants, my father said little about his life in Germany. We know that our grandfather, Benno, was a tobacco merchant. We learned shortly before our father passed in 2007 that, before leaving Germany, our grandfather had burned the tobacco fields (location unknown), not wanting the Nazis to profit from the fields.

We know from Volker Keller’s book, Bilder vom jüdischen Leben in Mannheim (Pictures of Jewish Life in Mannheim), that our father was a member of the Haschomer Hatzair Socialist-Zionist Youth Group. The book includes a group photo on page 120 with our then 12-year-old father that was taken in their apartment in 1934.

Socialist-Zionist Youth Mannheim 1934, Kurt Freudenthal is seated fourth from right

We know that our father, who was a sportswriter in Indianapolis for more than 50 years, participated in track and field as a youth. However, it wasn’t until he died that we learned he was a spectator at the 1936 Berlin Olympics track and field events. We know that our sister, Karolyn, was named for our great-grandfather, Kaufmann Freudenthaler. We also know that our father walked through the rubble of the destroyed synagogue (shortly after Kristallnacht) where he had celebrated his Bar Mitzvah, three years prior. Finally, we know that after immigrating to the United States, he never again stepped foot into Germany.

Selma Rosenfeld

A few months after our father had passed, I received an email from Michael Heitz, a school teacher/counselor in Eppingen, Germany, who was working with his students on a joint project between the University of Jewish Studies Heidelberg and four schools in the Kraichgau region to research and document Jewish culture in the Kraichgau.

Tracie and Linda in front of Selma-Rosenfeld-Realschule

In conjunction with the research project, Michael’s students campaigned to have Eppingen name the Realschule (middle school) in memory of Selma Rosenfeld, a former student and teacher in Eppingen (a town in the Kraichgau region). Selma had immigrated to the United States in 1924, received her master’s degree from UC Berkeley, and became a Professor of German in the Foreign Language Department at the Los Angeles City College, where she taught from 1930 until her retirement in 1958. Michael shared that Selma was the half-niece of our grandfather, Benno. He was trying to reach our father to gather additional information about Selma for the school dedication. He also informed me that our great-grandfather, Kaufmann Freudenthaler, had owned a Ratskeller (restaurant) in Eppingen, where Selma and our grandfather, Benno, were born.

Although we were unable to provide Michael with any information about Selma, he kindly sent me the booklet and map Jüedisches Leben Im Kraichgau created by the students, documenting Jewish Life in the Kraichgau. He also included photographs of his students, the Selma-Rosenfeld-Realschule, and a couple of postcards of the ‘Freudenthaler house’ (no longer standing) in Richen, which is part of Eppingen. I kept all his correspondence and shared the documents with my sisters and our cousins.

Once my sister Linda decided to accompany me on this journey, I reached out to Michael to share our plans, not knowing after 11 years if his email address was still good. Fortunately, my email did reach him and he offered to show us the Jewish historical sites in the area where our ancestors had lived. We planned to meet at the Sinsheim-Hoffenheim train station, a 40-minute train ride from Mannheim, on Sun., March 24th.

Tracing the tribe

In addition to contacting Michael, I also posted on the ‘Tracing the Tribe’ Facebook group my plans to travel to Mannheim for the Stolperstein dedication, asking if there were any members of the group from Mannheim. To my delight, Susan Salms-Moss reached out to me. Susan, currently residing in NYC, lived in Mannheim for more than 30 years. She initially went to Europe to study music, became a world class soprano, married, and raised two daughters in Mannheim. Today, she provides text translation services.

In her first email since connecting through Facebook, she had asked my father’s family name and what street they had lived on in Mannheim. Coincidentally, one of her daughters currently lives a block away on the same street. Susan became an invaluable resource and friend whom I look forward to meeting in person! She connected me to her friends and family in Mannheim, and provided all kinds of tips and advice as we prepared for this journey. She also introduced me by email to Dr. Manfred Loimeier, a professor at Heidelberg University who is also an editorial coordinator at the Mannheimer Morgen, the daily regional paper. It seemed there was interest in our trip to Mannheim for the Stolperstein dedication.

Shortly before we left for Germany, I was contacted by Lisa Wazulin, a staff writer at the Mannheimer Morgen, to inquire if she could set up an interview prior to the dedication. Due to our tight schedule and the paper wanting to publish the story before the Stolperstein dedication, I suggested we meet for coffee before our Monday morning “new” synagogue tour or meet at the synagogue. With my permission, she contacted the synagogue and arranged to join us on the tour. We sat down after the tour for the interview. Our story appeared in the following morning’s paper the day of the Stolperstein ceremony. We are grateful to Susan for translating the article from German to English for us, so we could read and share it with family and friends. To request a copy of the translated newspaper article, email Tracie at tgmrakich@sbcglobal.net.

Tracing our roots

On Sun., March 24th, we met Michael Heitz at the Sinsheim-Hoffenheim station as planned. This is one of the train stations where 6,551 Jews from the former regions of Baden and the Palatinate were deported to Gurs, in Vichy, France (at the foot of the Pyrenees), on Oct. 22, 1940. They were loaded onto seven trains for the two-day and two-night trip. Had our father, Kurt, Aunt Susan and our grandparents, Benno and Kate, not fled Germany after Kristallnacht, they would have been on one of those trains. Those who survived the brutal living conditions at the Gurs internment camp were later transported to, and murdered at Auschwitz.

Hoffenheim Gurs Memorial

When the Hoffenheim train station was renovated, the students from the Albert Schweitzer Schule in Sinsheim were instrumental in the creation of a monument made from two of the large rectangular stones from the train station. Located about a block away from the train station, the monument is in remembrance of the 18 Jewish Hoffenheim deportees to Gurs. In addition to the monument, a plaque at the former Hoffenheim town hall commemorates the 18 former Jewish residents – 14 who died at Auschwitz and four children who survived because their parents were able to send them from the Gurs camp to an orphanage in France. Later, some of the children were smuggled out of France through the underground or stayed with the underground fighters. There is also a marker where the Hoffenheim Synagogue stood before being destroyed on Kristallnacht.

In nearby Simsheim-Steinsfurt, we visited a building that was formerly a synagogue (built in 1893–94). It survived only because the building was sold before Kristallnacht. Inlaid in the stones adjacent to the building are tiles commemorating the various groups that were persecuted and deported from Steinsfurt to the death camps: Jews, Roma (gypsies), homosexuals, those of other religions, political foes, forced workers; and those with mental or physical issues who were the first to be “euthanized” by the Nazis. Inside the building, the name of one of our relatives, Ludwig Freudenthaler, is included on a plaque in remembrance of all the Jewish soldiers from Steinsfurt who served in the German army during WWI.

Tracie and Linda with Eppingen Mayor Klaus Holaschke

After Steinsfurt, we made a brief stop in the old farming village of Eppingen-Richen, where our great-grandfather was born and the Freudenthaler house once stood. It was here that we met the honorable Lord Mayor of Eppingen, Klaus Holaschke, who was out riding his bicycle. Michael explained to Mayor Holaschke why we were visiting and later shared with us that the mayor is deeply engaged in preserving the Jewish heritage of Eppingen and the Kraichgau area.

From Richen, we headed to the Jewish Cemetery in Eppingen, established in 1819. Before the trip, I had searched findagrave.com to see if we had ancestors buried in this cemetery. I found several ancestors and, to my surprise, learned that our great-great-great-grandfather Ascher Schmay Freudenthaler had adopted the name “Freudenthaler” in 1809. Schmay was Ascher’s father’s name. When I asked Michael about this, he explained that, in 1809, Jews were given the right to have “inheritable names,” and Ascher chose “Freudenthaler” for a nearby town. Interestingly, Ascher Schmay Freudenthaler is not buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Eppingen because he died in 1816, three years before the Eppingen cemetery was established.

Tracie at the gravestone of her great-grandparents Kaufmann and Bertha (Wolf) Freudenthaler

Below are some Freudenthaler ancestors, mostly from Richen, buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Eppingen – year of death in parenthesis:

• Great-grandparents: Kaufmann Freudenthaler (1913) and Bertha Wolf Freudenthaler (1925)

• Great-great-grandparents: Joseph Hirsch Freudenthaler (1872) and Rachael Stiefel Freudenthaler (1862)

• Great-great-great Grandmother: Johanna Freudenthaler (1855) who was married to great-great-great-grandfather: Ascher Schmay Freudenthaler (buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Heinsheim – 1816)

• Great aunt and uncle: Jette Freudenthaler-Hanauer (1882) and Lowe “Yehuda” Hanauer (1865); their son, Hermann Hanauer (1884)

• Great uncle and aunt: Ascher Freudenthaler (1901) and Hannchen Haber Freudenthaler (1892); their son, Aron Freudenthaler (1912) his wife Sofie Baer Freudenthaler (1937); their daughter Karoline Freudenthaler (1876); grandsons Ludwig (1928) and Julius (1936) Freudenthaler (Aron and Sofie’s sons)

Lunch at the Ratskeller in Eppingen with Michael Heitz

After visiting the cemetery, we had lunch at the Ratskeller in Eppingen, located a short walk from the town hall. This was the restaurant that was owned by our great-grandfather, Kaufmann. The Ratskeller was the first and only restaurant in Eppingen that was run by a Jewish family from 1876 until 1924. It was surreal. The furnishings have not changed over the years. I felt like I had stepped back in time to the 1920s. The food was delicious – we ordered turkey schnitzel and spaetzle with gravy. I finally found a beer that I liked that is local to the area – Palmbräu Unser Bestes, which is brewed next to the Ratskeller. Unfortunately to my knowledge it is not available in the USA!

After lunch, we explored Eppingen, which mostly escaped the bombings during WWII. The old part of Eppingen is a beautiful town with preserved unique half-timbered buildings dating back to the early 15th century. We stopped by the “Alte Universität” which hosted parts of the Heidelberg University in the years 1564–65 due to the black plague. The “Alte Universität” was also known as the “Alte Judenschule” (old Jewish School), where regular school for the Jewish children of the town took place during the early 19th century.

Sephardic Wedding Stone

We then walked to the old synagogue (built in 1774) where a beautiful Sephardic wedding stone that was hidden away during the Nazi reign adorns the outside of the building. From an outside door, we entered the basement to see the medieval mikvah. The mikvah was rediscovered in the late 1970s and then restored. It is one of the seven oldest mikvot in Germany. Like other still standing synagogue buildings, it was sold in the late 1890s and was no longer used as a synagogue. The Jewish community of Eppingen had built a new, beautiful neo-romantic style synagogue. The new synagogue, inaugurated in 1873, was destroyed during Kristallnacht.

After touring Eppingen, Michael took us to his home in nearby Sinsheim-Weiler, located on the footsteps of the Steinsberg tower (highest point of the Kraihgau area) to meet his lovely wife, Margit, and enjoy coffee and homemade apple cake. We presented Michael and Margit the tin of hamantashen plus an IU Hoosiers T-Shirt! They were very excited to receive the hamantashen.

Hamantashen for Margit and Michael Heitz

After cake and coffee, I brought out the photo album and sports photos with German writing on the back to see if either Michael or Margit could translate them for us. Because the writing was in “old German,” it was difficult to read. Michael was extremely interested in the photos and asked to scan them for his archives. Michael and Margit’s backyard has a wonderful view of Mount Steinsberg with its medieval castle. The yard is filled with fruit trees and backs up to a vineyard that was established in 1150. Before he took us back to the train station, Michael gave us a bottle of “Weilermer Steinsberg” 2016 Späetburgunder from the vineyard. It was hard to say our goodbyes, but we made plans to meet Michael for lunch on Wednesday in Strasbourg, France, since he would be there for a conference.

Monday, March 25th: Monday morning, we walked to the “new” synagogue, about 20 minutes from our hotel. There we met Marlies, who is a member of the synagogue board, and Lisa Wazulin, staff writer, and the photographer from the Mannheimer Morgen.

I dreaded the interview because we had so little information about our father’s life in Mannheim. Fortunately, Marlies came to our rescue, explaining to Lisa that our lack of knowledge is common among the second generation survivors. Lisa’s story, “Following Their Father’s Traces” focused on how we came to Mannheim for the Stolperstein dedication and to gain a better understanding of our family’s roots. She also wrote about what we had experienced so far on our journey.

Article from the German newspaper Mannheimer Morgen by reporter Lisa Wazulin that appeared the day of the ceremony.

Prior to WWII, the Jewish population in Mannheim was around 6,000, with multiple synagogues serving the Jewish community. Members of Mannheim’s Jewish community who did not or could not immigrate before October of 1940 were rounded up in the Gurs deportation. Today, there is only the “new” synagogue with roughly 400 members, half of whom had emigrated from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s.

We started our tour of the synagogue in the foyer, where there is a section of the interior wall built from stones that came from the destroyed synagogue and one special red-colored stone from Auschwitz. The photographer took our photo by the plaque on the wall that reads:

“Day and night, we wept for the martyrs of my people. – Jeremiah VIII.

We wistfully commemorate all the Jewish people who were persecuted, humiliated and murdered in the years of the National Socialist terror 1933 – 45.”

The synagogue was busy, as staff and volunteers were preparing for their annual Spring Ball the following Saturday evening. While we were there, a school group was learning about Judaism in the sanctuary. The synagogue hosts two to three school groups a week and community events throughout the year, both to educate the younger generations and to be a part of the greater community.

New Synagogue in Mannheim

We joined the students in the beautiful sanctuary to take a few photographs. While there is no wall separating the women from the men that you would find in an Orthodox synagogue, the women sit separately from the men – either on the sides of the main floor of the sanctuary, or upstairs overlooking the sanctuary.

While Jewish girls at the “new” synagogue may have Bat Mitzvahs, they differ from Bat Mitzvahs held at reform and conservative synagogues in the United States. They do not read the Torah or chant the Haftorah, as orthodox tradition forbids women from having contact with these holy items. According to Susan, a Bat Mitzvah girl at the “new” synagogue usually merely gives a speech thanking her parents and then has a party. For this reason, Susan’s daughters prepared for their Bat Mitzvahs long distance, and then celebrated their Bat Mitzvahs in the United States.

Monday evening, we met Orna, a friend of Susan’s in our hotel lobby. Orna was born in Tel Aviv. Her father immigrated to Palestine in 1936 from Kaiserslautern, Germany. Her mother was born in Drohobycz, near Lemberg, Poland, which is now the Ukraine. In 1956, Orna’s father moved the family back to Germany. Orna and her husband, Bernd, have three daughters. One daughter lives in Tel Aviv, and her two other daughters live in Mannheim. Next year, the family will celebrate a Bar Mitzvah in Mannheim. Orna took us to a nice restaurant overlooking the Rhine. Maybe because we were emailing each other before our visit, meeting Orna was like meeting family. Orna and Bernd received the second tin of Hamantashen.

Tues., March 26th – the Stolperstein dedication

There were 23 Stolperstein dedications scheduled. Ours was the last one that day. The apartment building was a short walk around the block from our hotel. We arrived at 3:45 p.m., for the 4:05 p.m., scheduled time. We knew that Orna and Bernd would attend but had no idea how many others would be there – especially since our story had appeared in the morning paper. Approximately 15 people had shown up for our dedication – Jewish and Christian. I had brought along my small photo album in case any of the attendees were interested in learning a little bit about the lives we were honoring. Plus, I was still trying to learn about the sporting event photographs.

Artist Gunter Demnig arriving for Stolperstein dedication

Gunter Demnig was running about 45 minutes late, but we were all busy talking to each other and didn’t mind the wait. We met a woman who traveled from Israel to attend the Stolperstein dedication for her relative, Matilde Wolff. Matilde was deported to Gurs and had perished in Auschwitz.

We met Evi, who thought that our father might have attended school with her father. Evi runs a hotel and restaurant near the train station that has been in her family since 1906. The hotel was destroyed during the war, like so many buildings in Mannheim. We traded phone numbers, and Evi sent me her father’s class picture to see if I could find our father. Unfortunately, we were unable to identify him. She also invited us to dinner at her hotel restaurant the next evening.

We met Klaus, who lived around the corner. Klaus was in his late 80s or early 90s. As a child living in Ludwigshafen across the Rhine from Mannheim, he remembers with shame the day the Jewish families were rounded up. His mother told him to stay away from the window.

We met Martin, who teaches at the Johanna-Geissmar-Gymnasium, a college preparatory school. Martin was also involved with the school research project and instrumental in renaming his school for Dr. Johanna Geissmar, who was deported in the Gurs transport and murdered at Auschwitz. Martin, we learned, had contacted Michael Heitz that evening to tell him that he had met us. It truly is a small world!

We also met Barbara, who is originally from Minnesota. Barbara lives nearby and has lived in Mannheim for 40 years. She shared that there are several Stolpersteine in the neighborhood. I asked her if there were any problems with the stones being desecrated. To her knowledge, none have been harmed. Barbara volunteered to be our translator at the dedication and the reception that followed.

Gunter Demnig preparing to place our Stolpersteine.

Once Gunter Demnig arrived wearing his trademark wide-brimmed hat and knee pads, he immediately got to work, removing the stone, digging out some of the dirt, and leveling the ground. He added small rocks for drainage and placed two rectangular and one square stone, before placing the four Stolpersteine with our family’s information engraved on the brass plates. After the stones were in place, he poured fine sand between the gaps and brushed away the residual sand. The whole process took less than ten minutes. Gunter does not say anything with words, yet his deeds speak volumes.

I did not think it would be emotional, but I was wrong. I only wish that our sister, Karolyn, and our cousins, Norman and Jeffrey, had joined us on this journey. (I did record it for their viewing.) After the stone placement, I had the opportunity to speak. I thanked everyone for attending and told them how important it was for my sister, Linda, and me to represent the Freudenthaler family at the Stolperstein dedication. I shared that including the two of us, there are 18 descendants of Kurt and Suse Freudenthaler; and how 18 was a significant number, as 18 is spelled with the Hebrew letters Chet (ח) and Yud (י), to form “Chai,” which is the Hebrew word for “life”.

Linda gazing at the installed Stolpersteine

Following the ceremony, we walked as a group to the local school for the reception. The Mannheim Stolperstein coordinator, Rolf Schönbrod, said a few words and introduced a teacher and two of her students. The students had raised money to cover the costs of some of the stones where there was no living family to help with the costs. Each stone costs 120 euros (approximately $135). We also heard from a representative from the Mannheim Mayor’s office. In between each speech, a pianist played solemn music. As we were leaving the reception, Orna introduced us to Volker Keller. Volker had written the book, Bilder vom jüdischen Leben in Mannheim (Pictures of Jewish Life in Mannheim) which contains the group photo with our father referenced earlier in the “What we know” section of this article.

Volker was extremely interested in the photos and asked if he could get copies. It was during our conversation with Volker that Orna solved the mystery of the sporting event photographs. She had noticed the letters “B” and “K” written on the back of some of the photos. They were from Bar Kochba sporting events! Our dad, who loved track and field, was active in the Bar Kochba Sports Club! As Michael Heitz had already scanned the photos, it was easy for Volker to obtain digital copies. Volker will be adding the photos to the Mannheim Jewish community archives. It will be interesting to see if any of our photos are included in a future book on Jewish life in pre-war Mannheim.

Wed., March 27

Prior to taking the train to Strasbourg, France, for the day, I met Jessica, Susan’s daughter, for coffee. Jessica lives down the street from our family’s former apartment. We talked about growing up in Mannheim and why she returned after graduating from Brandeis University. Like so many of us, she fell for a boy! Jessica was excited to receive the last tin of hamantashen. We had a short but enjoyable time getting to know each other, and I look forward to seeing her again. I regret that we were unable to go to Fermac’s, the Irish Pub that Jessica’s husband, Frank, owns. As the old saying goes, “There’s always next time” (and there will be a next time).

Dinner at Goldene Gans in Mannheim

Upon returning from Strasbourg, we enjoyed a special ‘last night in Mannheim’ dinner at the Goldene Gans Hotel located a short walk from the train station. Evi and her husband, Jürgen, treated us like family. We also met Evi’s sister Julia, and her nephew, Frieder. Frieder’s mother, Christiane, whom we did not get to meet, is an Ohio State graduate. We enjoyed getting to know Evi and her family and were treated to a delicious meal prepared by their son, Chef Felix, and served by Bettina. It was a nice way to cap off a trip of a lifetime.

This journey came together thanks to Susan, with whom I corresponded for months, and Michael and Orna, with whom I corresponded for weeks, before we flew to Frankfurt. I hope that someday I will be able to “pay it forward” for other second or third generation Holocaust survivors who are interested in placing Stolpersteine for their relatives. Perhaps someone who reads this article in The Jewish Post & Opinion, or stumbles upon it on the internet, will be inspired to follow in our footsteps to honor their family member(s) with a Stolperstein.

www.stolpersteine.eu/en/home/

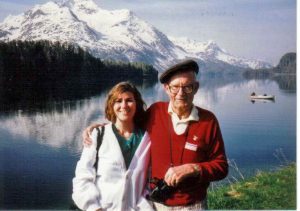

Tracie on a tour of Switzerland with her father Kurt Freudenthal in 1994.

Tracie Freudenthal-Mrakich grew up in Indianapolis and spent 18 years in the Los Angeles area (Pasadena) working in sales and marketing before moving back home to Indianapolis in 1999.

See her review of The German-Jewish Cookbook: Recipes and History of a Cuisine. By Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman and Sonya Gropmanat: https://jewishpostopinion.com/?p=3468